The metric system is a decimal (base-10) system of measurement built on standard units—metres, kilograms, seconds—designed to be universal, rational, and reproducible. In short: everyone measures the same thing, the same way, without needing a family tree of inches.

That idea sounds obvious. It took several millennia to get there.

Before metrics: bodies, barleycorns, and bafflement

Origin/context.

The earliest measurements were anthropocentric. That is, based on the human body or whatever happened to be lying around. Lengths were cubits (elbow to fingertip), feet, palms, and hands. Weights were seeds and stones. Time was about the sunrise.

This worked well enough until trade expanded beyond the local village. Your foot, alas, is not my foot and, neither was Pharaoh’s.

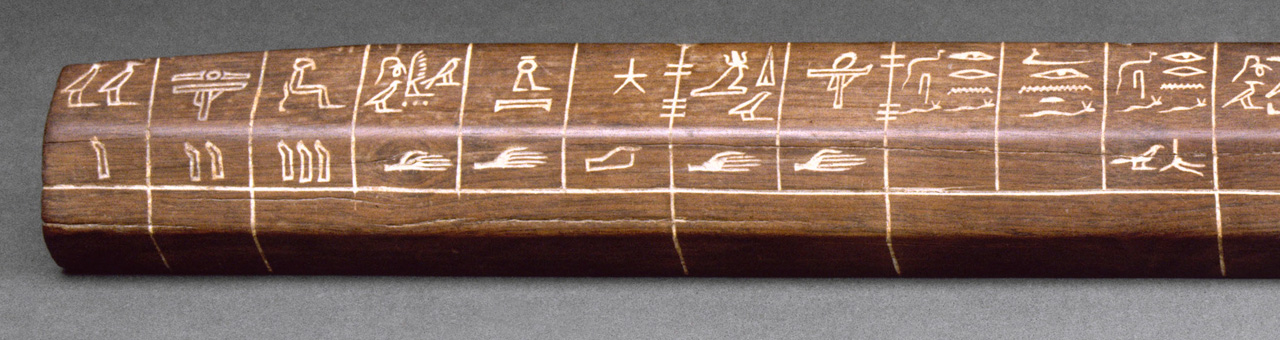

Ancient civilisations tried to impose order. Egypt standardised the royal cubit; Rome defined feet, miles, and pounds. Medieval Europe inherited the names and promptly multiplied the meanings. A ‘pound’ in one town could be 12 ounces, in another 16, and in a third; whatever the guild says today.

How it worked.

Local authorities kept physical standards. They kept metal rods, stones, balances; often locked in churches or town halls. Markets were inspected; disputes were common; cheating was endemic.

Why it mattered.

Measurement chaos isn’t quaint. It taxes trade, distorts prices, and quietly rewards the loudest ruler. When units vary, those in power fills the gaps.

The Enlightenment: what if numbers behaved?

Origin/context.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, science had developed an inconvenient habit of requiring precision. Astronomers, surveyors, and engineers wanted measurements that scaled cleanly and could be reproduced anywhere.

Enter Enlightenment rationalism, and with it, revolutionary France.

After 1789, France decided not only to redesign government but to tidy up reality. Hundreds of regional measures were abolished. In their place would be one system, based on nature, not kings or body parts.

How it worked.

A metre was defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole along a meridian through Paris. (This was ambitious, heroic, and, inevitably, slightly wrong, but the principle is what mattered.).

A kilogram was the mass of a cubic decimetre of water. Everything scaled by tens: millimetres, kilometres; grams, kilograms. Arithmetic replaced folklore.

Why it mattered.

For the first time, measurement was conceptually democratic. Anyone, anywhere, could, in theory, recreate the standard.

From platinum bars to physics itself

Origin/context.

Early metric standards were physical objects: platinum bars and cylinders stored under glass. These were marvellous, but they had a flaw. Objects can be scratched, lost, or (awkwardly) weigh slightly more on humid days.

As science advanced, so did the ambition: units should be defined not by artefacts, but by invariants of nature.

How it works today.

Modern SI units are defined by fixed physical constants: the speed of light, Planck’s constant, atomic transitions. The metre is no longer a bar in Paris; it is now how far light travels in a fraction of a second. Reality itself does the measuring.

Why it matters.

This makes the system universal in the strongest sense. Aliens with lasers and clocks could, in principle, agree with us.

Resistance, and polite chaos

Context.

Not everyone welcomed the metric system. It felt abstract, foreign, and suspiciously French. Britain flirted, adopted selectively, and now lives in a state of charming numerical bilingualism. The United States never quite signed the emotional paperwork (see our post on paper sizes).

Yet science, medicine, engineering, and global trade quietly standardised on metric because it works.

Practical takeaway.

If you want clarity, scalability, and fewer arguments in spreadsheets, use metric. If you want character, tradition, and to argue about teaspoons, you know what to do.

The long view

Why it matters, finally.

The metric system is not just about numbers. It is a rare example of humanity agreeing, across borders, languages, and centuries, on a shared abstraction. It replaces local power with shared reference. That is no small thing.

Is it perfect? Not entirely. Is it elegant? Undeniably. For something devised during a revolution and refined by committee, it does a great impression of common sense.

Leave a Comment

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you would like to, please leave a comment below.